Concerning the culture of La Réunion, the island you grew up on, we speak of »creole« culture. How do you think about the term »creolité« in your theoretical work? Do you find it fruitful for the postcolonial debate?

I rather use creolization than creolité. Creolization speaks of a dynamic process. It cannot be a thing of the past, it is still in the making. Will the society of La Réunion be open to new migrants? To people from the Comoros island, from Madagascar? They bring new forms of creolization, new transformations, new words, new sounds, and new cultural and political voices. Creolization cannot entail privatization, it is a process from below, it was born in the plantation, among exploited people confronted with cultural and linguistic hegemony, which they subverted.

About the notion of »poscoloniality«: we could say that the island is »postcolonial« in the sense that the colonial status ended in 1945, but it's still in a colonial relation to the French State. The State has the power, it has the final word, there is no autonomy whatsoever, or if there is, it remains within the limits imposed by the State. We can say, following South American theorists that there is a »coloniality of power«. There is still structural racism, white supremacy. We are in the Indian Ocean and yet under French and European laws that barely take into account our situation: a tropical island, a former slave society, on an Africa/Asia axis. True, we have representatives at the European parliament and the French parliament, but the overseas territories and their people do not exist in their consciousness. There is little understanding of what's happening. I would put »postcolonial« in parentheses, because otherwise it erases the current colonial situation.

In La Réunion, these political debates have often been linked to music. In the 70s the traditional Maloya-music was connected to the communist party and then forbidden, since 2009 it got on the UNESCO-list of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity. How do you see this development?

Of course, music and language and also rituals and food, continue to be a field of non-assimilation. A source, a reference and a field of resistance. In the 70s Maloya was on this side, it was never being performed in public because it was seen by the white Creoles and the State as backward, too »black«. The inscription on the UNESCO-list of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity was a double-edged sword, it promoted the music (that is also a ritual) but also integrated it into »world music«. The State integrated Maloya, as a proof of liberal multiculturalism, which does not address inequalities and injustices, exploitation, and dispossession. It is »music washing« we could say, it pacifies.

Multiculturalism is window-dressing, an advertisement for neo-liberal antiracism: »look how we are tolerant, how we are not racists!«. It also promotes the idea that there is no structural racism in Réunion – because we are »multicultural«. It transforms the idea of »Batarsité«, of creolization from below into a commodity for tourism and the French State benevolence whereas the later has never confronted structural racism. It gives to the State what people from below created: the »reunionnese« society.

But there are artists in La Réunion who offer a very vibrant and extremely lively field. There is a tradition of singers – men and women as well – that has emerged, that constitutes a very important source of thought and of expression.

The band »Saodaj« with Sami Pageaux Waro, an important voice of the younger generation of Maloya

You were mentioning sources before, and I wanted to ask because, you've been an activist your whole life, where do you find sources of hope?

There’s always hope. Not optimism or pessimism, but radical hope. There is an incredible and vast library of resistance through songs, poetry, theory, literature… an incredible imaginary that gives me hope everyday. I got interested in the “afterlives of slavery” very early and it was clear that the slaves and enslaved never stopped fighting. Never, ever. Their struggle lasted centuries but they never gave up. There is not a day without a struggle somewhere. There is not a day without women, men, workers, indigenous are standing and saying »No, this will not be like that.« The aspiration and dream for freedom is stronger than anything. I think we need a clear vision and imagination of how a better future could look like. This is what is art is about, too.

In 2000 you imagined a »museum without objects« in La Réunion, the Maison des civilizations et de l’unité réunionnaise (MCUR). It was stopped ten years later, when the Conversatives got the power. Do you want to talk about it, and can you tell more about the concept you had in mind?

The objective was to celebrate all the people who had »made« that island and made it different. The space we proposed was the Indian Ocean and this incredible connection between Africa and Asia and the Muslim worlds which existed long before the arrival of the Europeans. One idea was, as you mentioned, »a museum without objects«. The Western Museum fetishizes the object, so if you don't have an object, it is as if there was no life, no presence.

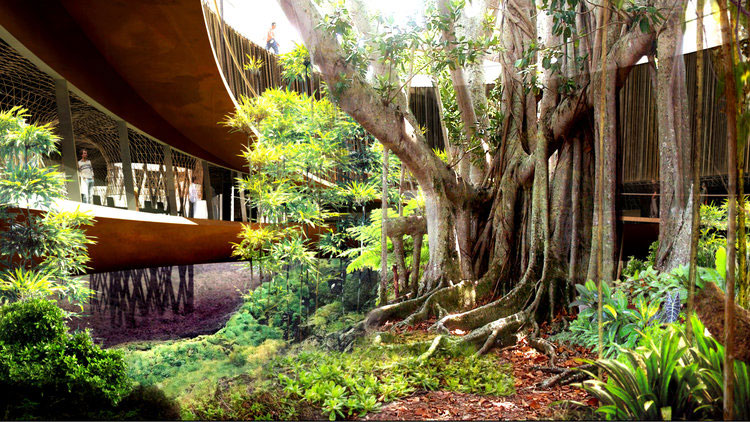

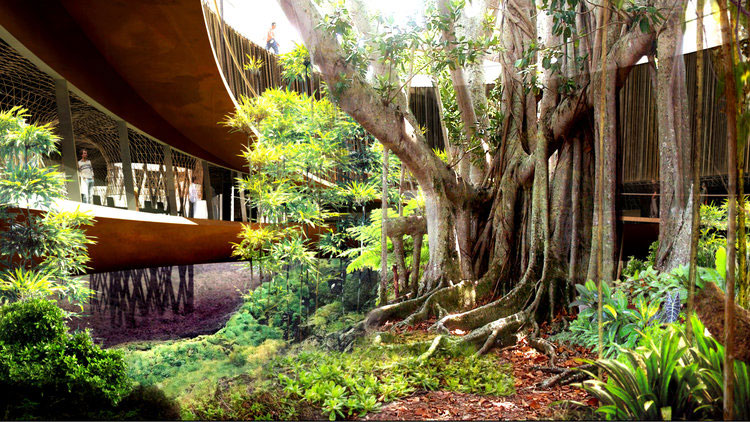

Maison des civilisations et de l’unité réunionnaise

Maison des civilisations et de l’unité réunionnaise

When we say »no object« we meant that we will not start from the object, but from the narrative. Power did not preserve objects from the slaves and enslaved, the indentured, the poor, the migrants, their lives did not matter, nor their creations and yet the later survived despite a will of erasure through language, music, food, rituals, names of mountains… It would have been from narratives that the lives of the oppressed would be told by using the technologies of theatre, cinema, performance, storytelling in the tradition of La Réunion. The space would not have been organized in a linear way that would have taken you inevitably to »progress« within the French State but in a circular way of constant reinvention and creation for the present and the future. The last room would have been a venue of the present time, where people would have been invited to imagine and say what they wanted in education, agriculture, culture, crafts, arts, industry, food, trade... It would have been a space for constant thinking and imagining… It would not have been a »museum« in the Western sense but a space providing elements for discussions and debates in conversation with people. There would have been a recording studio for people who would want to contribute -, thinking »Oh, I want to tell the story of my aunt, of my grandfather…. Not a recording just for the archive but to nourish thinking…. These were some of the ideas.

We didn’t want to have a rigid separation »nature« and »culture«. We borrowed form an architecture that exists from Africa to Asia, with the house around the garden. We paid attention to the climate and rejected air conditioning and we asked the architect to imagine an architecture in which the breezes will circulate, no artificial light either – in a land where you have so much natural light!

We paid attention to the way people circulate, what the popular classes expect from a public space. Poor women had told me that they were never welcomed in public places, not only because of the employees’ attitude but also because the way the space is conceived which always imposes a hierarchy of race, gender and class. It imposes a way of circulating and a kind of discipline. We allowed a lot of spaces where people could seat and chat. We also wanted to have all the languages which had been spoken on the island to be heard, not just Creole, French and English, but also Swahili, Malagasy, Urdu, Tamil, Cantonese, or French of the 17th century. These languages were spoken on the island and people did not lose their language when they arrived! Malagasy slaves did not stop to speak Malagasy, workers from Tamil Nadu didn’t stop to speak Tamil. And we suggested that there would not be systematic translation.

We trained a team of 20-30 young Reunionese that would have taken over the museum, once it opened. We did not want to have a permanent exhibition, to be able to change exhibits without a huge cost, that was very important, to be flexible.

As the regional election in 2010 was coming closer, around 2008, 2009, the project was under full attack. It was an attack on the political project, because the conservatives and part of the institutional left were afraid. They spoke of »anti-white racism«, even Reunion intellectuals, artists and historians attacked the project. They were afraid of new things, of building something that would have been totally autonomous from French norms. The local cultural representatives of the French state were against it. The attacks came daily: newspapers, radio, internet, social networks, television, propaganda. During the campaign, the candidate of the right party said: »If I'm elected, one of my first decisions will be to stop that project and to fire everyone.« And he fulfilled this promise.

It's a very sad story.

It was a big defeat. A huge defeat. Well, it was the erasure of ten years of work. The enemies were quite smart in the way they attacked the museum: »We need housing more than a museum.« You know, as if they were more lefty than the left. »We already have museums, why do we need one more?«.

The project was supported by people like Stuart Hall, Aimé Césaire, Maryse Condé, Jacques Derrida, Isaac Julien, and others. A lot of people worldwide expressed a deep interest. The project disappeared, was erased.

Did you already talk to museums in Europe, too? Many former ethnological museums are in big transformative processes.

I'm quite often invited by museums but outside of France. In my last book »Program of Absolute Disorder - Decolonize the Museum« I argue that the decolonization of the Western Museum is impossible: it is a colonial institution, built on colonialism and on racial thinking and so on. The Western Museum’s guidelines of conservation and the way museums are built today follow Western norms of preservation and architecture.

They have started to restitute some objects but that does not mean the place itself is decolonized. The Decolonial Museum is yet to be invented. And for me, again, »the imagination of tomorrow« is a very interesting part of what we discussed earlier: »What kind of institution do we want?« In a post-racist, post-capitalist society, what would be our institution? Because we cannot just say »this is bad«. What would we do? Do we still want museums? The space in which we preserve and transmit… What if we don't want to call it museum? The necessity of thinking about our own institutions is very urgent today.

Maybe we could try an analogy to concert places, to concert halls, to how to decolonize a festival?

First of all it’s important to ask questions, to imagine! For instance, how would be the decolonial music auditorium? In the 18th century, people listened while standing, eating, chatting, today we listen silently, we’re seated… We might come to the conclusion that we want to keep the silence and have another space that works differently next to it. But we have to think about it, through all possibilities while remaining open. For me, it's not just »oh, let's get rid of that«. Because then what? Those who are the enemies of any transformation are afraid of imagination. We should not be afraid… ¶

Concerning the culture of La Réunion, the island you grew up on, we speak of »creole« culture. How do you think about the term »creolité« in your theoretical work? Do you find it fruitful for the postcolonial debate?

I rather use creolization than creolité. Creolization speaks of a dynamic process. It cannot be a thing of the past, it is still in the making. Will the society of La Réunion be open to new migrants? To people from the Comoros island, from Madagascar? They bring new forms of creolization, new transformations, new words, new sounds, and new cultural and political voices. Creolization cannot entail privatization, it is a process from below, it was born in the plantation, among exploited people confronted with cultural and linguistic hegemony, which they subverted.

About the notion of »poscoloniality«: we could say that the island is »postcolonial« in the sense that the colonial status ended in 1945, but it's still in a colonial relation to the French State. The State has the power, it has the final word, there is no autonomy whatsoever, or if there is, it remains within the limits imposed by the State. We can say, following South American theorists that there is a »coloniality of power«. There is still structural racism, white supremacy. We are in the Indian Ocean and yet under French and European laws that barely take into account our situation: a tropical island, a former slave society, on an Africa/Asia axis. True, we have representatives at the European parliament and the French parliament, but the overseas territories and their people do not exist in their consciousness. There is little understanding of what's happening. I would put »postcolonial« in parentheses, because otherwise it erases the current colonial situation.

In La Réunion, these political debates have often been linked to music. In the 70s the traditional Maloya-music was connected to the communist party and then forbidden, since 2009 it got on the UNESCO-list of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity. How do you see this development?

Of course, music and language and also rituals and food, continue to be a field of non-assimilation. A source, a reference and a field of resistance. In the 70s Maloya was on this side, it was never being performed in public because it was seen by the white Creoles and the State as backward, too »black«. The inscription on the UNESCO-list of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity was a double-edged sword, it promoted the music (that is also a ritual) but also integrated it into »world music«. The State integrated Maloya, as a proof of liberal multiculturalism, which does not address inequalities and injustices, exploitation, and dispossession. It is »music washing« we could say, it pacifies.

Multiculturalism is window-dressing, an advertisement for neo-liberal antiracism: »look how we are tolerant, how we are not racists!«. It also promotes the idea that there is no structural racism in Réunion – because we are »multicultural«. It transforms the idea of »Batarsité«, of creolization from below into a commodity for tourism and the French State benevolence whereas the later has never confronted structural racism. It gives to the State what people from below created: the »reunionnese« society.

But there are artists in La Réunion who offer a very vibrant and extremely lively field. There is a tradition of singers – men and women as well – that has emerged, that constitutes a very important source of thought and of expression.

The band »Saodaj« with Sami Pageaux Waro, an important voice of the younger generation of Maloya

You were mentioning sources before, and I wanted to ask because, you've been an activist your whole life, where do you find sources of hope?

There’s always hope. Not optimism or pessimism, but radical hope. There is an incredible and vast library of resistance through songs, poetry, theory, literature… an incredible imaginary that gives me hope everyday. I got interested in the “afterlives of slavery” very early and it was clear that the slaves and enslaved never stopped fighting. Never, ever. Their struggle lasted centuries but they never gave up. There is not a day without a struggle somewhere. There is not a day without women, men, workers, indigenous are standing and saying »No, this will not be like that.« The aspiration and dream for freedom is stronger than anything. I think we need a clear vision and imagination of how a better future could look like. This is what is art is about, too.

In 2000 you imagined a »museum without objects« in La Réunion, the Maison des civilizations et de l’unité réunionnaise (MCUR). It was stopped ten years later, when the Conversatives got the power. Do you want to talk about it, and can you tell more about the concept you had in mind?

The objective was to celebrate all the people who had »made« that island and made it different. The space we proposed was the Indian Ocean and this incredible connection between Africa and Asia and the Muslim worlds which existed long before the arrival of the Europeans. One idea was, as you mentioned, »a museum without objects«. The Western Museum fetishizes the object, so if you don't have an object, it is as if there was no life, no presence.

Maison des civilisations et de l’unité réunionnaise

Maison des civilisations et de l’unité réunionnaise

When we say »no object« we meant that we will not start from the object, but from the narrative. Power did not preserve objects from the slaves and enslaved, the indentured, the poor, the migrants, their lives did not matter, nor their creations and yet the later survived despite a will of erasure through language, music, food, rituals, names of mountains… It would have been from narratives that the lives of the oppressed would be told by using the technologies of theatre, cinema, performance, storytelling in the tradition of La Réunion. The space would not have been organized in a linear way that would have taken you inevitably to »progress« within the French State but in a circular way of constant reinvention and creation for the present and the future. The last room would have been a venue of the present time, where people would have been invited to imagine and say what they wanted in education, agriculture, culture, crafts, arts, industry, food, trade... It would have been a space for constant thinking and imagining… It would not have been a »museum« in the Western sense but a space providing elements for discussions and debates in conversation with people. There would have been a recording studio for people who would want to contribute -, thinking »Oh, I want to tell the story of my aunt, of my grandfather…. Not a recording just for the archive but to nourish thinking…. These were some of the ideas.

We didn’t want to have a rigid separation »nature« and »culture«. We borrowed form an architecture that exists from Africa to Asia, with the house around the garden. We paid attention to the climate and rejected air conditioning and we asked the architect to imagine an architecture in which the breezes will circulate, no artificial light either – in a land where you have so much natural light!

We paid attention to the way people circulate, what the popular classes expect from a public space. Poor women had told me that they were never welcomed in public places, not only because of the employees’ attitude but also because the way the space is conceived which always imposes a hierarchy of race, gender and class. It imposes a way of circulating and a kind of discipline. We allowed a lot of spaces where people could seat and chat. We also wanted to have all the languages which had been spoken on the island to be heard, not just Creole, French and English, but also Swahili, Malagasy, Urdu, Tamil, Cantonese, or French of the 17th century. These languages were spoken on the island and people did not lose their language when they arrived! Malagasy slaves did not stop to speak Malagasy, workers from Tamil Nadu didn’t stop to speak Tamil. And we suggested that there would not be systematic translation.

We trained a team of 20-30 young Reunionese that would have taken over the museum, once it opened. We did not want to have a permanent exhibition, to be able to change exhibits without a huge cost, that was very important, to be flexible.

As the regional election in 2010 was coming closer, around 2008, 2009, the project was under full attack. It was an attack on the political project, because the conservatives and part of the institutional left were afraid. They spoke of »anti-white racism«, even Reunion intellectuals, artists and historians attacked the project. They were afraid of new things, of building something that would have been totally autonomous from French norms. The local cultural representatives of the French state were against it. The attacks came daily: newspapers, radio, internet, social networks, television, propaganda. During the campaign, the candidate of the right party said: »If I'm elected, one of my first decisions will be to stop that project and to fire everyone.« And he fulfilled this promise.

It's a very sad story.

It was a big defeat. A huge defeat. Well, it was the erasure of ten years of work. The enemies were quite smart in the way they attacked the museum: »We need housing more than a museum.« You know, as if they were more lefty than the left. »We already have museums, why do we need one more?«.

The project was supported by people like Stuart Hall, Aimé Césaire, Maryse Condé, Jacques Derrida, Isaac Julien, and others. A lot of people worldwide expressed a deep interest. The project disappeared, was erased.

Did you already talk to museums in Europe, too? Many former ethnological museums are in big transformative processes.

I'm quite often invited by museums but outside of France. In my last book »Program of Absolute Disorder - Decolonize the Museum« I argue that the decolonization of the Western Museum is impossible: it is a colonial institution, built on colonialism and on racial thinking and so on. The Western Museum’s guidelines of conservation and the way museums are built today follow Western norms of preservation and architecture.

They have started to restitute some objects but that does not mean the place itself is decolonized. The Decolonial Museum is yet to be invented. And for me, again, »the imagination of tomorrow« is a very interesting part of what we discussed earlier: »What kind of institution do we want?« In a post-racist, post-capitalist society, what would be our institution? Because we cannot just say »this is bad«. What would we do? Do we still want museums? The space in which we preserve and transmit… What if we don't want to call it museum? The necessity of thinking about our own institutions is very urgent today.

Maybe we could try an analogy to concert places, to concert halls, to how to decolonize a festival?

First of all it’s important to ask questions, to imagine! For instance, how would be the decolonial music auditorium? In the 18th century, people listened while standing, eating, chatting, today we listen silently, we’re seated… We might come to the conclusion that we want to keep the silence and have another space that works differently next to it. But we have to think about it, through all possibilities while remaining open. For me, it's not just »oh, let's get rid of that«. Because then what? Those who are the enemies of any transformation are afraid of imagination. We should not be afraid… ¶

Wir nutzen die von dir eingegebene E-Mail-Adresse, um dir in regelmäßigen Abständen unseren Newsletter senden zu können. Falls du es dir mal anders überlegst und keine Newsletter mehr von uns bekommen möchtest, findest du in jeder Mail in der Fußzeile einen Unsubscribe-Button. Damit kannst du deine E-Mail-Adresse aus unserem Verteiler löschen. Weitere Infos zum Thema Datenschutz findest du in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

OUTERNATIONAL wird kuratiert von Elisa Erkelenz und ist ein Kooperationsprojekt von PODIUM Esslingen und VAN Magazin im Rahmen des Fellowship-Programms #bebeethoven anlässlich des Beethoven-Jubiläums 2020 – maßgeblich gefördert von der Kulturstiftung des Bundes sowie dem Land Baden-Württemberg, der Baden-Württemberg Stiftung und der L-Bank.

Wir nutzen die von dir eingegebene E-Mail-Adresse, um dir in regelmäßigen Abständen unseren Newsletter senden zu können. Falls du es dir mal anders überlegst und keine Newsletter mehr von uns bekommen möchtest, findest du in jeder Mail in der Fußzeile einen Unsubscribe-Button. Damit kannst du deine E-Mail-Adresse aus unserem Verteiler löschen. Weitere Infos zum Thema Datenschutz findest du in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

OUTERNATIONAL wird kuratiert von Elisa Erkelenz und ist ein Kooperationsprojekt von PODIUM Esslingen und VAN Magazin im Rahmen des Fellowship-Programms #bebeethoven anlässlich des Beethoven-Jubiläums 2020 – maßgeblich gefördert von der Kulturstiftung des Bundes sowie dem Land Baden-Württemberg, der Baden-Württemberg Stiftung und der L-Bank.